Fort William Holiday Lodge

historic highlands

The incredible History of Fort William, ScotlandThe History of Fort William, Scotland is truly fascinating and varied. Covering Clans, Continental Plates, Wars, Mountain Climbing & Industry. Below is a brief summary of all the best bits.

table of contents

The History of Fort William, Scotland

430-390 Million Years Ago

Fort William, Scotland Origins

Fort William, your gateway to the majestic Scottish Highlands, boasts a rich and fascinating history shaped by its dramatic landscape and strategic location at the start of the Great Glen. This vast valley, a defining feature of the region, was carved by powerful glacial erosion along the Great Glen Fault line over millions of years.

As you explore the surrounding Munros, consider that the Appalachian Mountains in the United States, the Scottish Highlands, the Mountains of Greenland and parts of Scandinavia were all once one connected mountain range.

As you explore the surrounding Munros, consider that the Appalachian Mountains in the United States, the Scottish Highlands, the Mountains of Greenland and parts of Scandinavia were all once one connected mountain range.

500 BC

Dun Deardail Fort

Just south of Fort William, overlooking Glen Nevis, lies the intriguing Iron Age fort of Dun Deardail. A rewarding walk takes you to this strategically positioned site, offering panoramic views.

While much about its purpose remains a mystery, evidence suggests it was a significant settlement, possibly the stronghold of a powerful local chief, dating back to at least 500 BC. Intriguingly, theories suggest the fort was intentionally burned at an incredibly high temperature, evidenced by melted rock.

While much about its purpose remains a mystery, evidence suggests it was a significant settlement, possibly the stronghold of a powerful local chief, dating back to at least 500 BC. Intriguingly, theories suggest the fort was intentionally burned at an incredibly high temperature, evidenced by melted rock.

127o

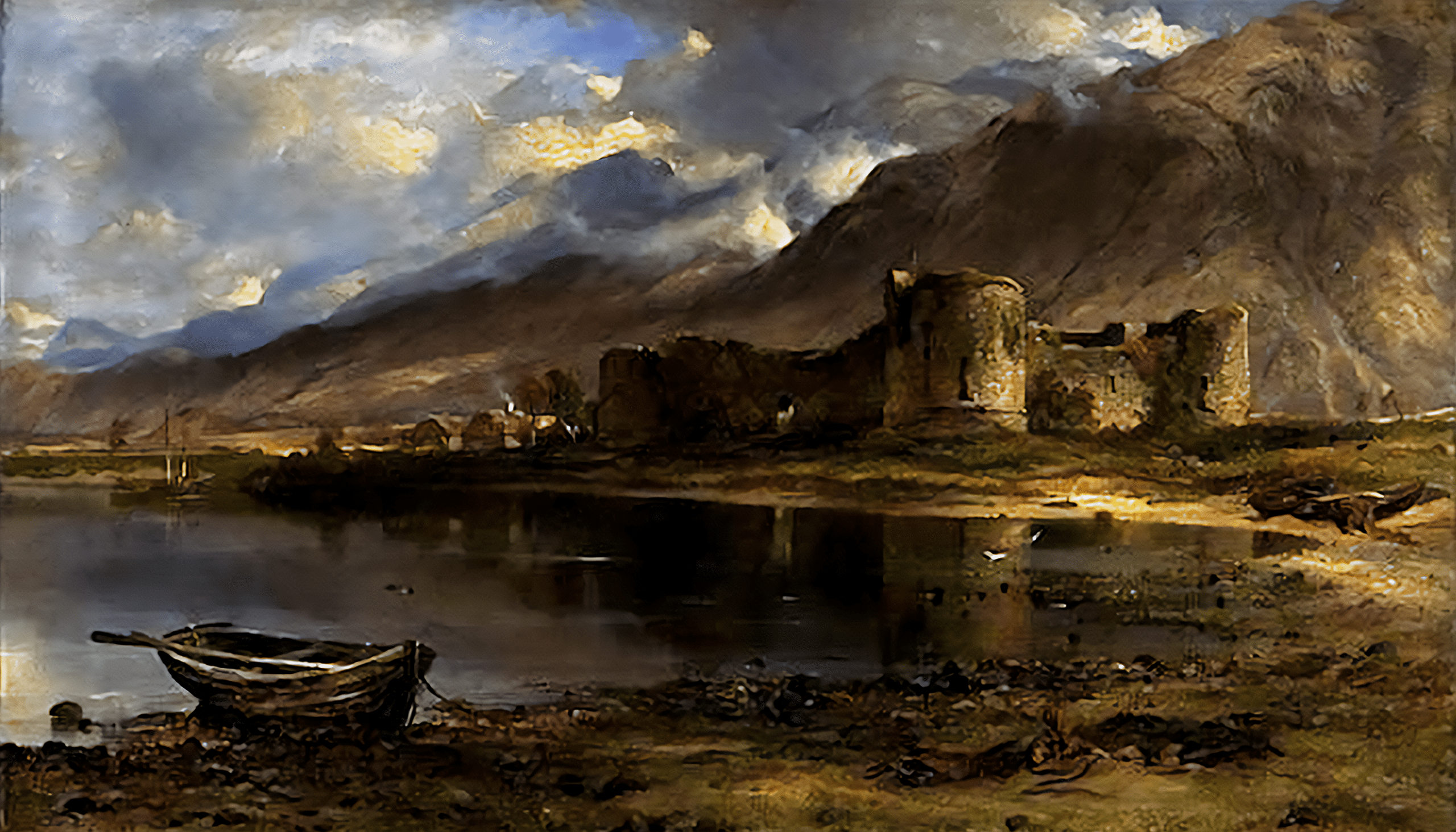

Inverlochy Castle

Located just north of Fort William, on the south bank of the River Nevis as it meets Loch Linnhe, lie the evocative ruins of Inverlochy Castle. The visible remains date back to a substantial stone castle constructed around 1270 by the Chief of the powerful Clan Comyn.

However, this strategic location may have been occupied even earlier, with potential evidence of a previous Pictish settlement. Adding to its ancient history, medieval historian Hector Boece (writing in the late 15th and early 16th centuries) documented a Viking destruction of a city believed to have been situated at this very site.

By the early 16th century (around 1501), Inverlochy Castle came under the control of Clan Cameron, who would become the dominant force in the Lochaber region.

Planning Your Visit: The ruins of Inverlochy Castle are easily accessible and offer a tangible link to the area’s medieval past. The site is located adjacent to the Highland Soap Company Cafe, providing a convenient opportunity for a break and refreshments – whether for breakfast, brunch, or lunch – during your historical exploration.

However, this strategic location may have been occupied even earlier, with potential evidence of a previous Pictish settlement. Adding to its ancient history, medieval historian Hector Boece (writing in the late 15th and early 16th centuries) documented a Viking destruction of a city believed to have been situated at this very site.

By the early 16th century (around 1501), Inverlochy Castle came under the control of Clan Cameron, who would become the dominant force in the Lochaber region.

Planning Your Visit: The ruins of Inverlochy Castle are easily accessible and offer a tangible link to the area’s medieval past. The site is located adjacent to the Highland Soap Company Cafe, providing a convenient opportunity for a break and refreshments – whether for breakfast, brunch, or lunch – during your historical exploration.

1410+

Clan Cameron: Lords of Lochaber

From the 15th century onwards, Clan Cameron held a position of significant power and influence in Lochaber, the historical region encompassing present-day Fort William and Ben Nevis.

One prominent figure in their early leadership was Donald Dubh Cameron (circa 1410), considered the first chief to be known as the Lochiel, a title that would become synonymous with the head of the clan.

The very name “Cameron” is believed to have originated from a distinctive personal trait of Donald Dubh – his crooked nose, or “Camshron” in Scottish Gaelic.

The rise of Clan Cameron’s dominance in Lochaber is also attributed in part to strategic alliances, such as Donald Dubh’s marriage to an heiress from the local Mael-anfhaidh kindred. The Gaelic name “Mael-anfhaidh” translates to “children of He who was dedicated to the storm,” a name hinting at the powerful forces of nature prevalent in this Highland region (we’ll explore the local climate further elsewhere on the site).

Exploring Clan Cameron History: For visitors interested in learning more about this influential Highland clan, two excellent resources are available:

The Clan Cameron Museum: This museum offers a dedicated insight into the history, heritage, and traditions of Clan Cameron.

The West Highland Museum: This museum also features exhibits detailing the history and impact of Clan Cameron within the broader context of the West Highlands.

One prominent figure in their early leadership was Donald Dubh Cameron (circa 1410), considered the first chief to be known as the Lochiel, a title that would become synonymous with the head of the clan.

The very name “Cameron” is believed to have originated from a distinctive personal trait of Donald Dubh – his crooked nose, or “Camshron” in Scottish Gaelic.

The rise of Clan Cameron’s dominance in Lochaber is also attributed in part to strategic alliances, such as Donald Dubh’s marriage to an heiress from the local Mael-anfhaidh kindred. The Gaelic name “Mael-anfhaidh” translates to “children of He who was dedicated to the storm,” a name hinting at the powerful forces of nature prevalent in this Highland region (we’ll explore the local climate further elsewhere on the site).

Exploring Clan Cameron History: For visitors interested in learning more about this influential Highland clan, two excellent resources are available:

The Clan Cameron Museum: This museum offers a dedicated insight into the history, heritage, and traditions of Clan Cameron.

The West Highland Museum: This museum also features exhibits detailing the history and impact of Clan Cameron within the broader context of the West Highlands.

1431

Battle of Inverlochy I

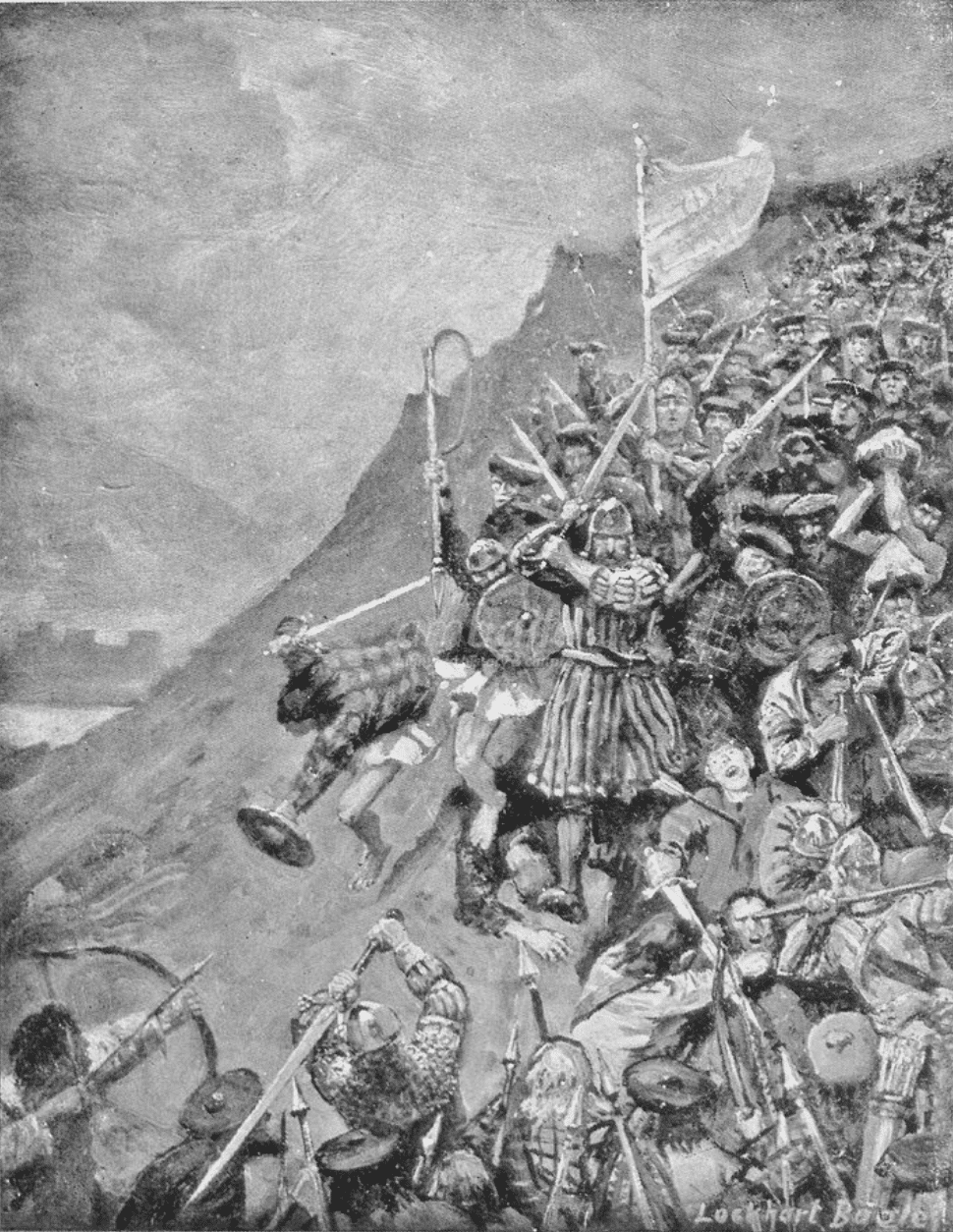

The year 1431 witnessed a significant conflict near Inverlochy Castle, fueled by the complex power dynamics of the Scottish Highlands.

Alexander of Islay, holding the influential titles of Earl of Ross and Lord of the Isles (a lordship with roots tracing back to the Viking era), was imprisoned by King James I.

This act sparked a powerful response from the Highlanders, who rallied behind the young Donald Balloch, just 18 years old, to lead Clan Donald.

Balloch and his forces confronted the Royalist army at Inverlochy Castle, resulting in a decisive victory for the Highland clans.

It is estimated that around 1000 Royalist defenders perished in the battle. Following this triumph, Donald Balloch sought retribution against local clans, specifically Clan Cameron and Clan Chattan, who were perceived as having shown disloyalty to Alexander of Islay.

In retaliation, King James I personally led an army into the Highlands, prompting Donald Balloch to seek refuge in Antrim, Ireland.

Historical Significance: This battle underscores the significant autonomy and power wielded by the Highland lords and clans during the 15th century, often operating outside direct royal control. The strategic location of Inverlochy Castle made it a focal point in these power struggles.

Alexander of Islay, holding the influential titles of Earl of Ross and Lord of the Isles (a lordship with roots tracing back to the Viking era), was imprisoned by King James I.

This act sparked a powerful response from the Highlanders, who rallied behind the young Donald Balloch, just 18 years old, to lead Clan Donald.

Balloch and his forces confronted the Royalist army at Inverlochy Castle, resulting in a decisive victory for the Highland clans.

It is estimated that around 1000 Royalist defenders perished in the battle. Following this triumph, Donald Balloch sought retribution against local clans, specifically Clan Cameron and Clan Chattan, who were perceived as having shown disloyalty to Alexander of Islay.

In retaliation, King James I personally led an army into the Highlands, prompting Donald Balloch to seek refuge in Antrim, Ireland.

Historical Significance: This battle underscores the significant autonomy and power wielded by the Highland lords and clans during the 15th century, often operating outside direct royal control. The strategic location of Inverlochy Castle made it a focal point in these power struggles.

1645

The Battle of Inverlochy II

During the tumultuous Scottish Civil War, January 1645 saw the strategic landscape around Fort William become the stage for a remarkable military manoeuvre.

Following the destruction of Inveraray, the stronghold of the powerful Campbells of Argyll, Royalist forces under the command of James Graham, the 1st Marquess of Montrose – renowned as ‘The Great Montrose’ – advanced towards Fort William.

Their journey took them through the rugged passes of Glencoe (a route similar to parts of the modern West Highland Way) and into Glen Nevis, before heading up the Great Glen with the aim of resupply.

However, Montrose faced a precarious situation. An army loyal to Argyll was positioned at the southern end of the Great Glen, at Inverlochy Castle, while another opposing force awaited at the northern end, near Inverness.

Faced with this pincer movement, Montrose executed one of the most celebrated flanking marches in Scottish history. His army traversed the exceptionally harsh terrain surrounding Ben Nevis in the depths of winter, a testament to their resilience and Montrose’s strategic brilliance.

After a grueling night spent in the challenging winter conditions on the slopes of Ben Nevis, Montrose’s audacious maneuver caught Argyll completely by surprise.

Expecting to encounter only a small contingent, Argyll instead found himself facing the entire Royalist force. He swiftly retreated to his galley anchored on Loch Linnhe, leaving the defense of Inverlochy Castle to Duncan Campbell.

Campbell positioned his experienced troops (many were veterans of the war in England) in front of the castle.

Just before dawn on February 2nd, Montrose launched his attack.

The Covenanter defenders were quickly overwhelmed and routed. Their retreat to the perceived safety of Inverlochy Castle was cut off by Montrose’s cavalry. Facing insurmountable odds, the garrison within the castle surrendered without further resistance.

The battle resulted in the loss of approximately 1500 Covenanter lives, while Montrose’s forces suffered significantly fewer casualties, around 250.

Historical Context: This battle is a compelling example of Montrose’s military genius and the strategic importance of the Fort William area during the Civil War. His daring march and decisive victory had a significant impact on the course of the conflict. Montrose himself was later defeated and executed in 1650, but his campaign around Ben Nevis remains a legendary feat of military history.

As you explore the landscapes around Fort William and Glen Nevis, you can appreciate the challenging terrain that played a crucial role in this pivotal event.

Following the destruction of Inveraray, the stronghold of the powerful Campbells of Argyll, Royalist forces under the command of James Graham, the 1st Marquess of Montrose – renowned as ‘The Great Montrose’ – advanced towards Fort William.

Their journey took them through the rugged passes of Glencoe (a route similar to parts of the modern West Highland Way) and into Glen Nevis, before heading up the Great Glen with the aim of resupply.

However, Montrose faced a precarious situation. An army loyal to Argyll was positioned at the southern end of the Great Glen, at Inverlochy Castle, while another opposing force awaited at the northern end, near Inverness.

Faced with this pincer movement, Montrose executed one of the most celebrated flanking marches in Scottish history. His army traversed the exceptionally harsh terrain surrounding Ben Nevis in the depths of winter, a testament to their resilience and Montrose’s strategic brilliance.

After a grueling night spent in the challenging winter conditions on the slopes of Ben Nevis, Montrose’s audacious maneuver caught Argyll completely by surprise.

Expecting to encounter only a small contingent, Argyll instead found himself facing the entire Royalist force. He swiftly retreated to his galley anchored on Loch Linnhe, leaving the defense of Inverlochy Castle to Duncan Campbell.

Campbell positioned his experienced troops (many were veterans of the war in England) in front of the castle.

Just before dawn on February 2nd, Montrose launched his attack.

The Covenanter defenders were quickly overwhelmed and routed. Their retreat to the perceived safety of Inverlochy Castle was cut off by Montrose’s cavalry. Facing insurmountable odds, the garrison within the castle surrendered without further resistance.

The battle resulted in the loss of approximately 1500 Covenanter lives, while Montrose’s forces suffered significantly fewer casualties, around 250.

Historical Context: This battle is a compelling example of Montrose’s military genius and the strategic importance of the Fort William area during the Civil War. His daring march and decisive victory had a significant impact on the course of the conflict. Montrose himself was later defeated and executed in 1650, but his campaign around Ben Nevis remains a legendary feat of military history.

As you explore the landscapes around Fort William and Glen Nevis, you can appreciate the challenging terrain that played a crucial role in this pivotal event.

1654

‘Fort William’

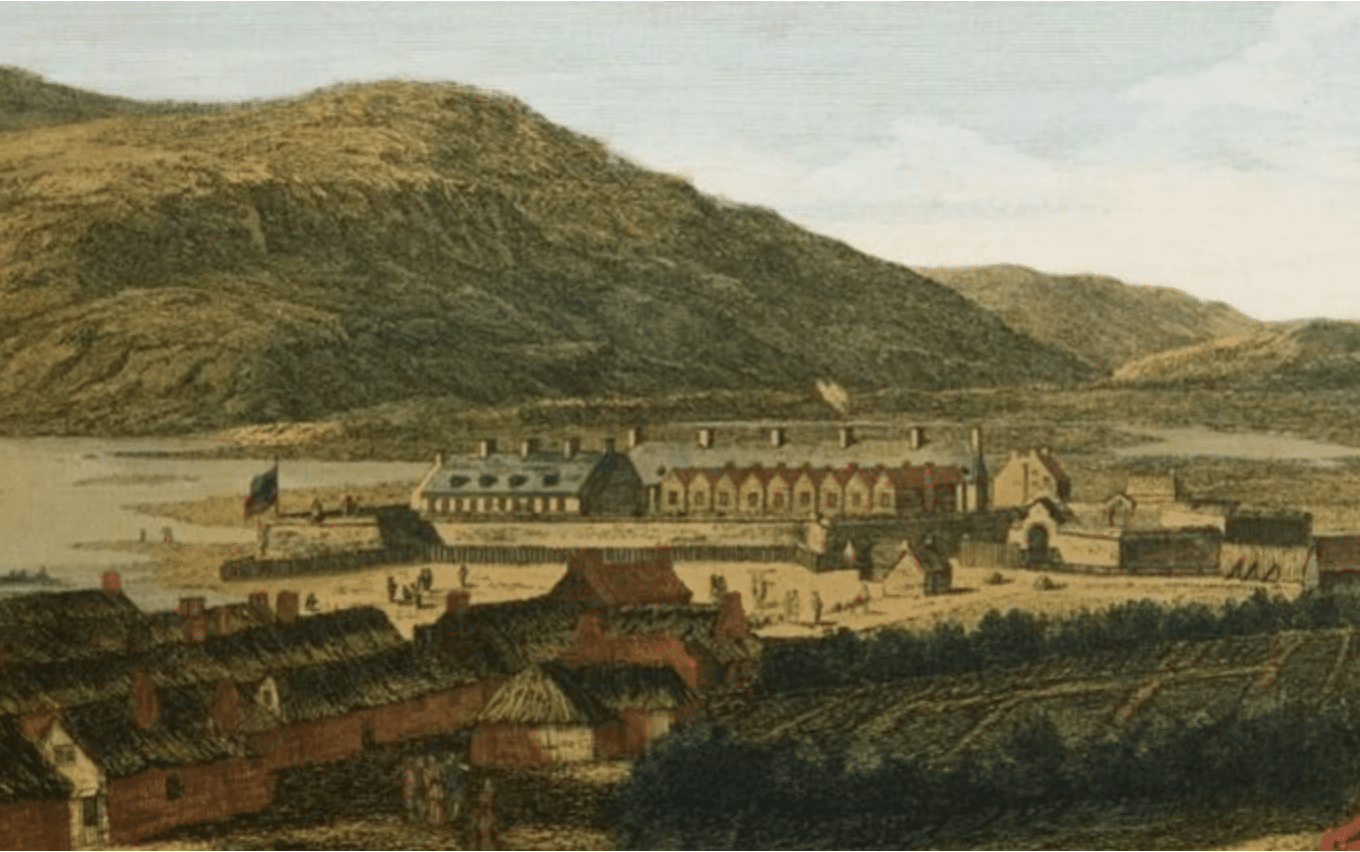

Following the tumultuous War of the Three Kingdoms, a significant step towards establishing a permanent presence in the Lochaber region occurred in 1654.

General George Monck, Oliver Cromwell’s Commander in Scotland, constructed a garrison at Inverlochy. This strategic move aimed to pacify the powerful Clan Cameron and maintain order in the area.

However, the more substantial stone fortification that would eventually lend its name to the town was built later, after the Glorious Revolution of 1688.

Under the direction of General Hugh MacKay, a more permanent fort was erected on the banks of Loch Linnhe, situated near the present-day Morrisons roundabout.

This new stronghold was named in honour of William of Orange, who became King William III of England, Scotland, and Ireland.

Interestingly, the naming of the town itself followed a slightly different path. Initially, the settlement that grew around the fort was called Maryburgh, in honour of King William’s wife, Queen Mary II. Over time, the town’s name evolved, briefly becoming Gordonsburgh and then Duncansburgh, before finally being named Fort William after Prince William, Duke of Cumberland.

Visiting the Old Fort: For those interested in exploring this historical site, the ruins of the later 17th-century Fort William are still accessible. You can park conveniently at the Morrisons supermarket and then carefully cross the roundabout to reach the area where the fort once stood.

General George Monck, Oliver Cromwell’s Commander in Scotland, constructed a garrison at Inverlochy. This strategic move aimed to pacify the powerful Clan Cameron and maintain order in the area.

However, the more substantial stone fortification that would eventually lend its name to the town was built later, after the Glorious Revolution of 1688.

Under the direction of General Hugh MacKay, a more permanent fort was erected on the banks of Loch Linnhe, situated near the present-day Morrisons roundabout.

This new stronghold was named in honour of William of Orange, who became King William III of England, Scotland, and Ireland.

Interestingly, the naming of the town itself followed a slightly different path. Initially, the settlement that grew around the fort was called Maryburgh, in honour of King William’s wife, Queen Mary II. Over time, the town’s name evolved, briefly becoming Gordonsburgh and then Duncansburgh, before finally being named Fort William after Prince William, Duke of Cumberland.

Visiting the Old Fort: For those interested in exploring this historical site, the ruins of the later 17th-century Fort William are still accessible. You can park conveniently at the Morrisons supermarket and then carefully cross the roundabout to reach the area where the fort once stood.

1692

The Glencoe Massacre

A tragic event that continues to resonate in Highland history is the Glencoe Massacre of 1692.

Approximately 30 members of Clan MacDonald of Glencoe were killed by government forces due to their perceived failure to pledge allegiance to King William II (William of Orange).

While the clan leaders had seemingly agreed to take the oath, disagreements over the distribution of indemnity payments led to a delay.

Adding to the misfortune, Maclain of Glencoe, the clan chief, travelled to Fort William to swear his allegiance only to find the designated official was not there, and he was subsequently instructed to travel to Inveraray.

The delay in the MacDonalds taking the oath provided an opportunity for the Scottish Secretary of State to make an example of the clan, influenced by existing clan politics and a long-standing reputation of the Lochaber area for lawlessness, including cattle raiding and theft, as perceived by the government, rival clans, and even contemporary Gaelic poets.

In January 1692, a company of around 120 men under the command of Captain Robert Campbell of Glenlyon arrived in Glencoe. Hospitality was extended by the MacDonalds, who provided the soldiers with accommodation and sustenance during their stay.

However, on February 12th, a chilling order was issued from Colonel John Hill in Fort William to Lieutenant Colonel James Hamilton. This order instructed Hamilton to take 400 men and block any potential escape route for the MacDonalds via Kinlochleven.

Simultaneously, another force of 400 men under Major Duncanson was to join Campbell’s men with the explicit instruction to kill all MacDonalds they encountered in the glen.

It is reported that Campbell’s men were kept unaware of the horrific plan until the early hours of February 13th. Under the cover of darkness and facing harsh winter conditions, some of the MacDonalds are said to have fled into the remote Lost Valley in a desperate attempt to escape the slaughter.

Remembering the Past: The Glencoe Massacre remains a significant and somber event in Scottish history, highlighting the complex political landscape and the often-brutal realities of the time.

As you travel through Glencoe, understanding this tragic history adds a deeper layer to the already dramatic scenery.

Approximately 30 members of Clan MacDonald of Glencoe were killed by government forces due to their perceived failure to pledge allegiance to King William II (William of Orange).

While the clan leaders had seemingly agreed to take the oath, disagreements over the distribution of indemnity payments led to a delay.

Adding to the misfortune, Maclain of Glencoe, the clan chief, travelled to Fort William to swear his allegiance only to find the designated official was not there, and he was subsequently instructed to travel to Inveraray.

The delay in the MacDonalds taking the oath provided an opportunity for the Scottish Secretary of State to make an example of the clan, influenced by existing clan politics and a long-standing reputation of the Lochaber area for lawlessness, including cattle raiding and theft, as perceived by the government, rival clans, and even contemporary Gaelic poets.

In January 1692, a company of around 120 men under the command of Captain Robert Campbell of Glenlyon arrived in Glencoe. Hospitality was extended by the MacDonalds, who provided the soldiers with accommodation and sustenance during their stay.

However, on February 12th, a chilling order was issued from Colonel John Hill in Fort William to Lieutenant Colonel James Hamilton. This order instructed Hamilton to take 400 men and block any potential escape route for the MacDonalds via Kinlochleven.

Simultaneously, another force of 400 men under Major Duncanson was to join Campbell’s men with the explicit instruction to kill all MacDonalds they encountered in the glen.

It is reported that Campbell’s men were kept unaware of the horrific plan until the early hours of February 13th. Under the cover of darkness and facing harsh winter conditions, some of the MacDonalds are said to have fled into the remote Lost Valley in a desperate attempt to escape the slaughter.

Remembering the Past: The Glencoe Massacre remains a significant and somber event in Scottish history, highlighting the complex political landscape and the often-brutal realities of the time.

As you travel through Glencoe, understanding this tragic history adds a deeper layer to the already dramatic scenery.

18th Century

Deforestation

By the 18th century, the once-extensive native woodlands of the Scottish Highlands had reached a critical point of decline.

These ancient “rainforests of the Highlands” had flourished around 6000 years ago, supporting a rich ecosystem that included species like Scots pine, aspen, birch, oak, rowan, holly, willow, and alder, alongside now-extinct or locally rare wildlife such as lynx, giant wild cattle, wolves, bears, and boars.

The decline of these woodlands was a gradual process. By the Roman era, approximately half of the original forest cover had been lost. In the medieval period, timber was a vital resource for shipbuilding and housing.

However, the 18th century witnessed a significant acceleration of deforestation during the Highland Clearances. Vast tracts of land were cleared to make way for large-scale sheep farming, dramatically altering the landscape.

While the prominence of sheep farming decreased during the Victorian era, a new factor hindered the regrowth of native trees: the rise in popularity of deer hunting as a sporting pursuit. This often led to the management of the land in ways that discouraged woodland regeneration to maintain open grazing for deer.

Understanding the Past, Appreciating the Present: As you explore the often open landscapes around Fort William and the wider Highlands, it’s important to remember this history of deforestation. Efforts are now underway to restore native woodlands, recognizing their ecological importance and historical significance.

Observing the remnants of older trees and the ongoing conservation initiatives provides a deeper understanding of the long-term human impact on this dramatic environment.

These ancient “rainforests of the Highlands” had flourished around 6000 years ago, supporting a rich ecosystem that included species like Scots pine, aspen, birch, oak, rowan, holly, willow, and alder, alongside now-extinct or locally rare wildlife such as lynx, giant wild cattle, wolves, bears, and boars.

The decline of these woodlands was a gradual process. By the Roman era, approximately half of the original forest cover had been lost. In the medieval period, timber was a vital resource for shipbuilding and housing.

However, the 18th century witnessed a significant acceleration of deforestation during the Highland Clearances. Vast tracts of land were cleared to make way for large-scale sheep farming, dramatically altering the landscape.

While the prominence of sheep farming decreased during the Victorian era, a new factor hindered the regrowth of native trees: the rise in popularity of deer hunting as a sporting pursuit. This often led to the management of the land in ways that discouraged woodland regeneration to maintain open grazing for deer.

Understanding the Past, Appreciating the Present: As you explore the often open landscapes around Fort William and the wider Highlands, it’s important to remember this history of deforestation. Efforts are now underway to restore native woodlands, recognizing their ecological importance and historical significance.

Observing the remnants of older trees and the ongoing conservation initiatives provides a deeper understanding of the long-term human impact on this dramatic environment.

18th & 19th centuries

Highland Clearances

The 18th and 19th centuries marked a period of significant social and economic upheaval across the Highlands, known as the Highland Clearances.

Driven primarily by the increasing profitability of large-scale sheep farming, local populations were systematically evicted from their ancestral lands.

This forced displacement led to widespread migration, with many Highlanders seeking new lives along the coasts, in the Lowlands of Scotland, or even overseas. North America became a major destination, with significant communities establishing themselves in places like Nova Scotia, Cape Breton, Ontario, and the Carolinas.

Against this backdrop of social change, the early 18th century saw the construction of a network of military roads throughout the Highlands under the direction of General George Wade, beginning around 1725.

These roads were built with the aim of improving government control and maintaining peace in what was often perceived as a “unruly” region by the authorities. Even today, as you explore the area around Fort William and the wider Highlands, you will notice roads still bearing the name “General Wade’s Road,” serving as a tangible reminder of this era and the government’s efforts to exert its influence.

Understanding the Impact: The Highland Clearances represent a deeply significant and often painful chapter in Scottish history. The impact of this period on the social fabric, Gaelic culture, and landscape of the Highlands was profound and continues to be a subject of historical study and remembrance.

Driven primarily by the increasing profitability of large-scale sheep farming, local populations were systematically evicted from their ancestral lands.

This forced displacement led to widespread migration, with many Highlanders seeking new lives along the coasts, in the Lowlands of Scotland, or even overseas. North America became a major destination, with significant communities establishing themselves in places like Nova Scotia, Cape Breton, Ontario, and the Carolinas.

Against this backdrop of social change, the early 18th century saw the construction of a network of military roads throughout the Highlands under the direction of General George Wade, beginning around 1725.

These roads were built with the aim of improving government control and maintaining peace in what was often perceived as a “unruly” region by the authorities. Even today, as you explore the area around Fort William and the wider Highlands, you will notice roads still bearing the name “General Wade’s Road,” serving as a tangible reminder of this era and the government’s efforts to exert its influence.

Understanding the Impact: The Highland Clearances represent a deeply significant and often painful chapter in Scottish history. The impact of this period on the social fabric, Gaelic culture, and landscape of the Highlands was profound and continues to be a subject of historical study and remembrance.

1745

Jacobite Rising

During the Jacobite Rising of 1745, Fort William found itself under siege by Jacobite forces between March 20th and April 3rd, 1746.

Following their successful capture of Fort Augustus and Fort George, the Jacobites aimed to secure Fort William as well.

Had they succeeded, this would have effectively linked the three key government fortifications along the strategic Great Glen, potentially bolstering their control of the region.

However, the government defenders within Fort William mounted a determined resistance and successfully repelled the Jacobite attempts to capture the stronghold.

This ultimately prevented the Jacobites from achieving their strategic goal of controlling the entire length of the Great Glen.

Historical Significance: The successful defense of Fort William represents a notable setback for the Jacobite cause during the ’45 rebellion.

It highlights the continued government presence and resistance in this key Highland location, even after significant Jacobite successes elsewhere.

Following their successful capture of Fort Augustus and Fort George, the Jacobites aimed to secure Fort William as well.

Had they succeeded, this would have effectively linked the three key government fortifications along the strategic Great Glen, potentially bolstering their control of the region.

However, the government defenders within Fort William mounted a determined resistance and successfully repelled the Jacobite attempts to capture the stronghold.

This ultimately prevented the Jacobites from achieving their strategic goal of controlling the entire length of the Great Glen.

Historical Significance: The successful defense of Fort William represents a notable setback for the Jacobite cause during the ’45 rebellion.

It highlights the continued government presence and resistance in this key Highland location, even after significant Jacobite successes elsewhere.

1771

First Recorded Ascent of Ben Nevis

The first recorded ascent of this iconic mountain was made on August 17th, 1771, by James Robertson. An Edinburgh-based botanist, Robertson’s primary motivation for his climb was to collect botanical specimens unique to the high-altitude environment of Lochaber.

Just a few years later, in 1774, John Williams successfully summited Ben Nevis and provided the first documented account of the mountain’s geological structure, contributing to early scientific understanding of the region.

Even renowned figures from other fields were drawn to conquer “The Ben.” In 1818, the famous English poet John Keats undertook the arduous climb. His vivid description of the ascent as akin to “mounting ten St. Pauls (cathedrals) without the convenience of a staircase” eloquently captures the scale and challenge of the undertaking, even in those early days.

Interestingly, despite its imposing presence, Ben Nevis was only officially confirmed as Britain’s highest mountain in 1847, following more accurate surveying and measurement.

A Legacy of Exploration: These early ascents mark the beginning of a long history of human interaction with Ben Nevis, from scientific inquiry to personal challenge. As you gaze upon or perhaps even climb this magnificent peak, consider the footsteps of these early explorers and their pioneering spirit. The Pony Track, a popular route to the summit today, likely follows paths used by some of these early adventurers.

Just a few years later, in 1774, John Williams successfully summited Ben Nevis and provided the first documented account of the mountain’s geological structure, contributing to early scientific understanding of the region.

Even renowned figures from other fields were drawn to conquer “The Ben.” In 1818, the famous English poet John Keats undertook the arduous climb. His vivid description of the ascent as akin to “mounting ten St. Pauls (cathedrals) without the convenience of a staircase” eloquently captures the scale and challenge of the undertaking, even in those early days.

Interestingly, despite its imposing presence, Ben Nevis was only officially confirmed as Britain’s highest mountain in 1847, following more accurate surveying and measurement.

A Legacy of Exploration: These early ascents mark the beginning of a long history of human interaction with Ben Nevis, from scientific inquiry to personal challenge. As you gaze upon or perhaps even climb this magnificent peak, consider the footsteps of these early explorers and their pioneering spirit. The Pony Track, a popular route to the summit today, likely follows paths used by some of these early adventurers.

1803

Neptune’s Staircase

Located in Banavie, just outside Fort William, Neptune’s Staircase is an impressive series of eight interconnected canal locks.

This remarkable feat of engineering, designed by the renowned Thomas Telford and constructed between 1803 and 1822, serves as a crucial link between Loch Linnhe and the Caledonian Canal.

By navigating a series of lochs along the Great Glen, the Caledonian Canal provides a navigable waterway connecting the Atlantic Ocean to the North Sea.

Neptune’s Staircase holds the distinction of being the longest staircase lock in Britain. Observing vessels pass through this system is a fascinating process, with boats typically taking around 90 minutes to traverse all eight locks.

Visiting Today: Neptune’s Staircase is not only a historical landmark but also a popular visitor attraction.

The area offers excellent opportunities for gentle walks along the scenic towpaths of the Caledonian Canal.

You can witness the impressive engineering firsthand and enjoy the tranquil waterside setting. It’s a great place to appreciate the ambition and scale of early 19th-century infrastructure projects in the Highlands.

This remarkable feat of engineering, designed by the renowned Thomas Telford and constructed between 1803 and 1822, serves as a crucial link between Loch Linnhe and the Caledonian Canal.

By navigating a series of lochs along the Great Glen, the Caledonian Canal provides a navigable waterway connecting the Atlantic Ocean to the North Sea.

Neptune’s Staircase holds the distinction of being the longest staircase lock in Britain. Observing vessels pass through this system is a fascinating process, with boats typically taking around 90 minutes to traverse all eight locks.

Visiting Today: Neptune’s Staircase is not only a historical landmark but also a popular visitor attraction.

The area offers excellent opportunities for gentle walks along the scenic towpaths of the Caledonian Canal.

You can witness the impressive engineering firsthand and enjoy the tranquil waterside setting. It’s a great place to appreciate the ambition and scale of early 19th-century infrastructure projects in the Highlands.

1883

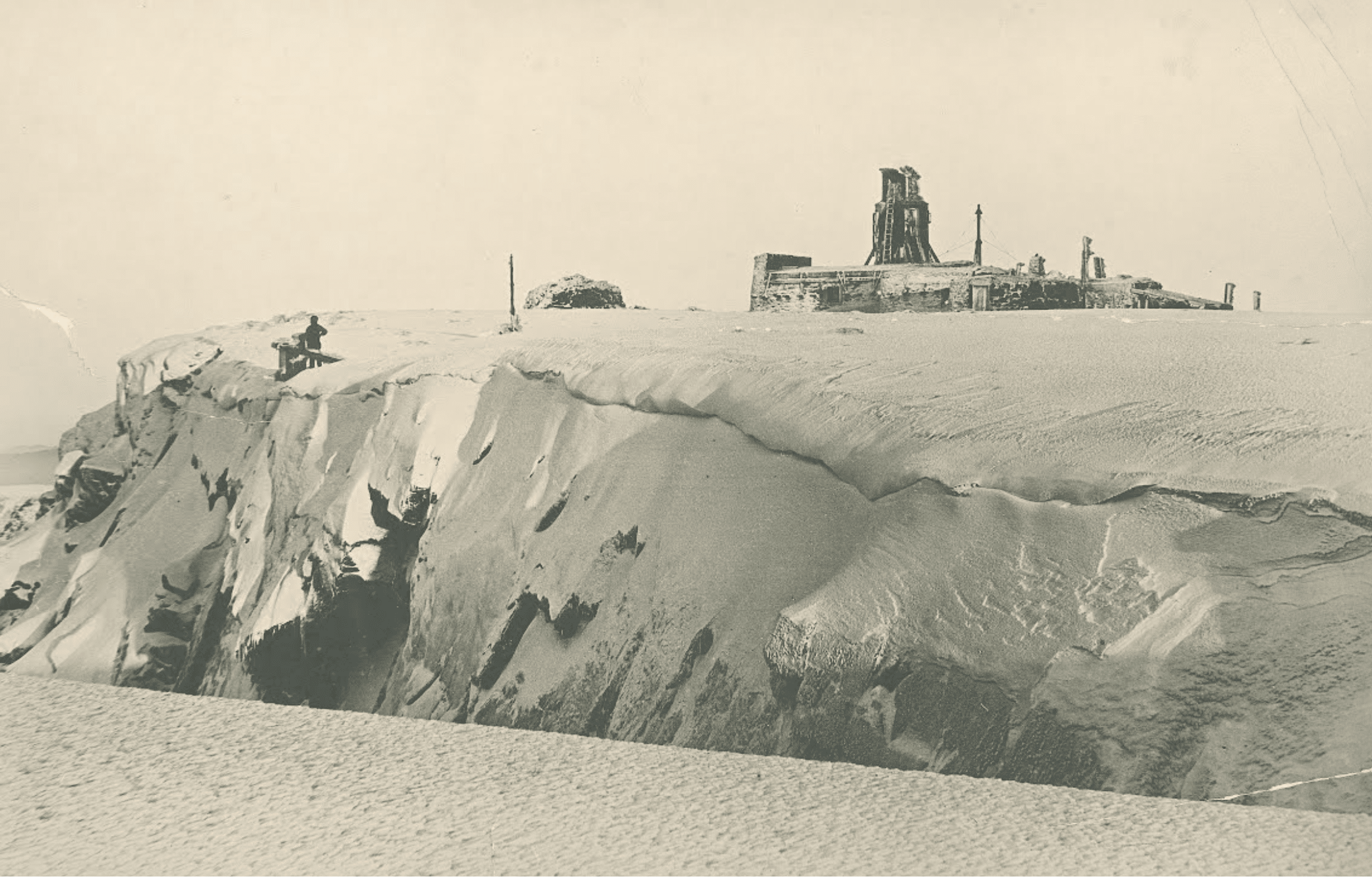

Ben Nevis Observatory

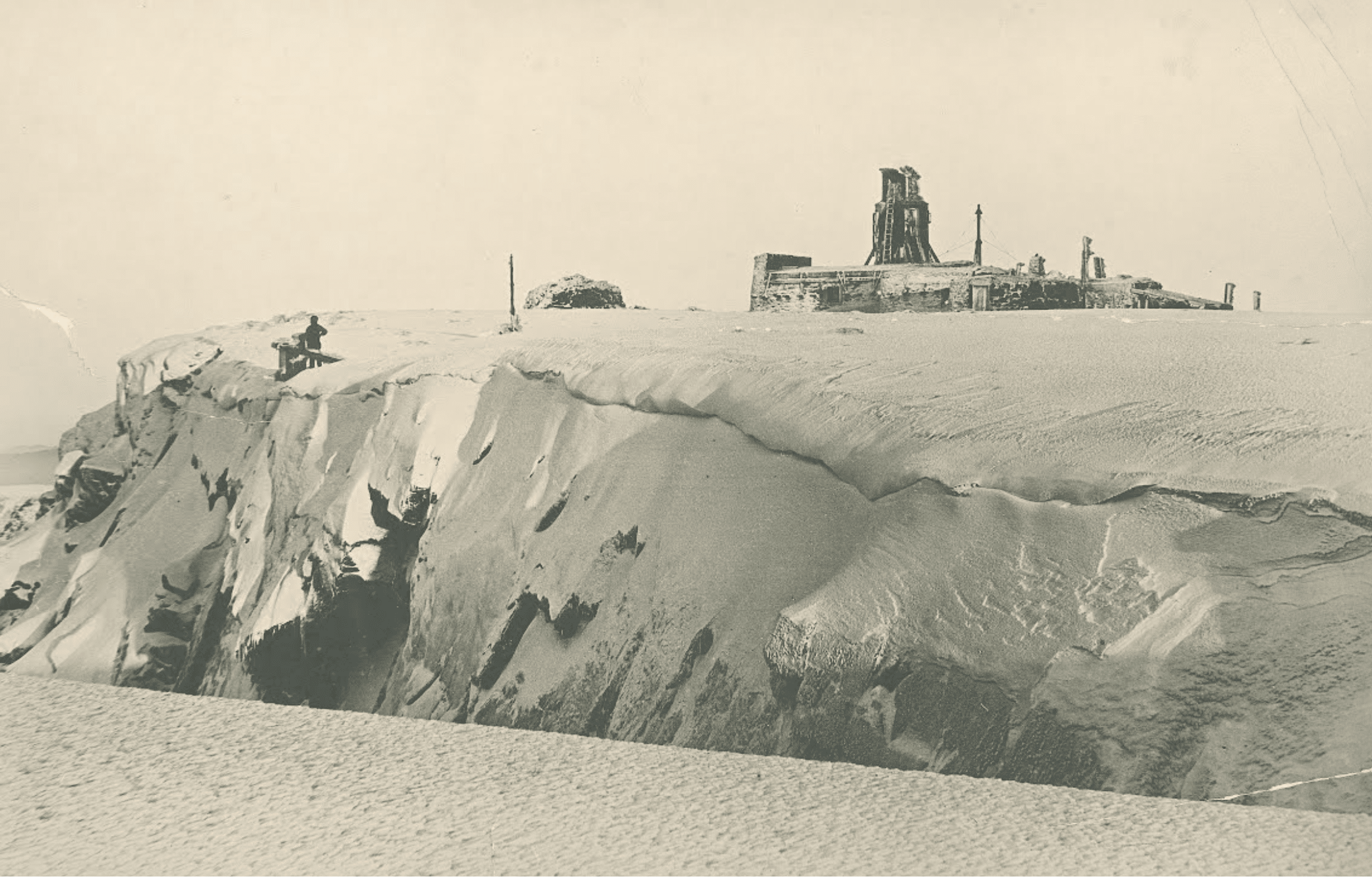

The prominent location of Ben Nevis, directly exposed to the powerful Atlantic storms, made it a scientifically significant site for weather observation in the late 19th century.

Recognizing this potential, the Scottish Meteorological Society sponsored pioneering research on the summit.

Between June 1st and mid-October 1881, Clement Wragge undertook an extraordinary feat, climbing Ben Nevis every single day, starting at 5 am, to take meteorological readings using instruments provided by the Society.

His dedication highlighted the challenging and often severe weather conditions prevalent on the mountain, a fact well-known to those living in the vicinity.

Wragge’s remarkable efforts garnered widespread public attention, leading to a successful nationwide fundraising appeal.

The funds raised supported two significant developments: the creation of the Pony Track, which remains a popular and well-maintained route to the summit from Glen Nevis today, and the construction of a permanent observatory on the summit.

Weather observations at the Ben Nevis Observatory commenced in November 1883 and continued until 1904. The data collected during this period remains invaluable, representing the most comprehensive continuous set of mountain weather records ever recorded in Great Britain.

Life at the summit observatory was demanding. Supplies were laboriously transported up the Pony Track by pack ponies.

The dedicated staff stationed there frequently faced the arduous task of digging themselves out of the observatory after severe winter storms.

Historical Significance: The Ben Nevis Observatory stands as a testament to early scientific endeavor in challenging environments. Its legacy provides crucial insights into Highland weather patterns and the dedication of early meteorologists.

As you ascend Ben Nevis via the Pony Track, consider the remarkable history of scientific research that took place on its summit.

Recognizing this potential, the Scottish Meteorological Society sponsored pioneering research on the summit.

Between June 1st and mid-October 1881, Clement Wragge undertook an extraordinary feat, climbing Ben Nevis every single day, starting at 5 am, to take meteorological readings using instruments provided by the Society.

His dedication highlighted the challenging and often severe weather conditions prevalent on the mountain, a fact well-known to those living in the vicinity.

Wragge’s remarkable efforts garnered widespread public attention, leading to a successful nationwide fundraising appeal.

The funds raised supported two significant developments: the creation of the Pony Track, which remains a popular and well-maintained route to the summit from Glen Nevis today, and the construction of a permanent observatory on the summit.

Weather observations at the Ben Nevis Observatory commenced in November 1883 and continued until 1904. The data collected during this period remains invaluable, representing the most comprehensive continuous set of mountain weather records ever recorded in Great Britain.

Life at the summit observatory was demanding. Supplies were laboriously transported up the Pony Track by pack ponies.

The dedicated staff stationed there frequently faced the arduous task of digging themselves out of the observatory after severe winter storms.

Historical Significance: The Ben Nevis Observatory stands as a testament to early scientific endeavor in challenging environments. Its legacy provides crucial insights into Highland weather patterns and the dedication of early meteorologists.

As you ascend Ben Nevis via the Pony Track, consider the remarkable history of scientific research that took place on its summit.

1894

West Highland Rail Line

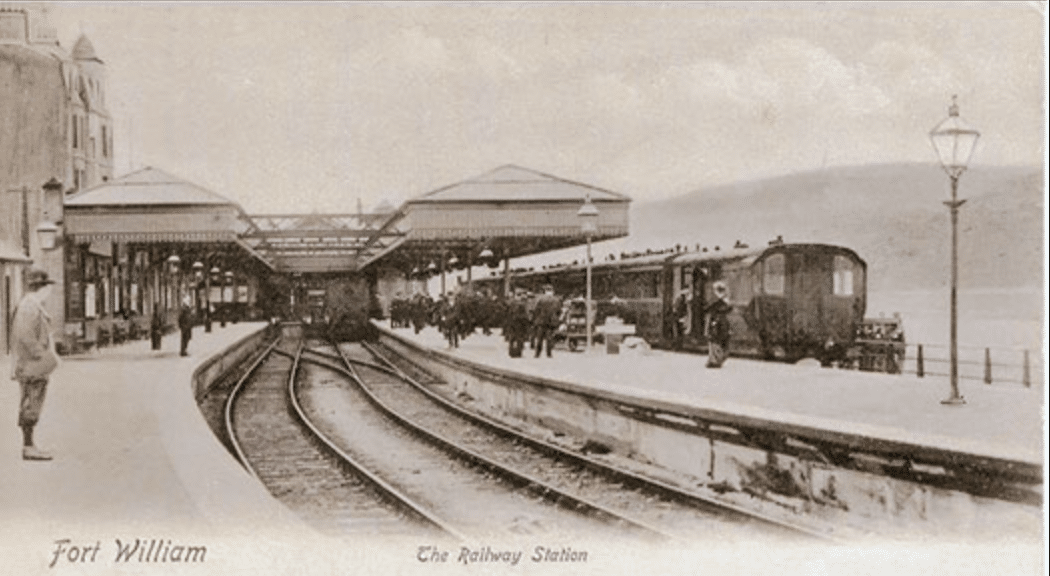

The arrival of the West Highland Railway in Fort William in 1894 marked a significant milestone, providing the town (and later Mallaig) with its first direct rail link to Glasgow and the wider network.

The original Fort William train station was strategically located alongside the town’s shipping pier, in the area now occupied by the dual carriageway next to Loch Linnhe, facilitating the transport of goods and passengers between rail and sea.

As the railway line extended westward from Fort William towards the fishing port of Mallaig, one of its most iconic structures, the Glenfinnan Viaduct, was completed in 1901. This impressive concrete viaduct, with its 21 arches, was a pioneering feat of engineering at the time of its construction.

Today, the Glenfinnan Viaduct enjoys global fame, largely due to its prominent role in the Harry Potter film series, where the Jacobite steam train is depicted crossing its majestic spans en route to Hogwarts.

The West Highland Line itself was recognized for its breathtaking scenery when it was voted the top rail journey in the world in 2009.

Experiencing History Today: One of the most popular and memorable experiences for visitors to Fort William is a journey on the Jacobite Steam Train to Mallaig.

This iconic train follows the historic route of the West Highland Line, offering unparalleled views of the stunning Highland landscapes, including Loch Eil and, of course, the Glenfinnan Viaduct.

It’s a fantastic way to step back in time and witness the scenery that made this railway line world-renowned. The regular ScotRail service also operates on this scenic route year-round.

The original Fort William train station was strategically located alongside the town’s shipping pier, in the area now occupied by the dual carriageway next to Loch Linnhe, facilitating the transport of goods and passengers between rail and sea.

As the railway line extended westward from Fort William towards the fishing port of Mallaig, one of its most iconic structures, the Glenfinnan Viaduct, was completed in 1901. This impressive concrete viaduct, with its 21 arches, was a pioneering feat of engineering at the time of its construction.

Today, the Glenfinnan Viaduct enjoys global fame, largely due to its prominent role in the Harry Potter film series, where the Jacobite steam train is depicted crossing its majestic spans en route to Hogwarts.

The West Highland Line itself was recognized for its breathtaking scenery when it was voted the top rail journey in the world in 2009.

Experiencing History Today: One of the most popular and memorable experiences for visitors to Fort William is a journey on the Jacobite Steam Train to Mallaig.

This iconic train follows the historic route of the West Highland Line, offering unparalleled views of the stunning Highland landscapes, including Loch Eil and, of course, the Glenfinnan Viaduct.

It’s a fantastic way to step back in time and witness the scenery that made this railway line world-renowned. The regular ScotRail service also operates on this scenic route year-round.

1911

Ford Model T Ascent of Ben Nevis

In a remarkable display of early automotive ambition and perseverance, Henry Alexander Jr successfully drove a Ford Model T to the summit of Ben Nevis in 1911.

His journey began in Edinburgh, bringing him to Torlundy (the location of Highwinds) and then on to Fort William, the base for his audacious attempt on the UK’s highest peak.

The ascent up the Pony Track from Glen Nevis was a significant undertaking, taking Alexander five days to reach the summit. Each day, he would leave the Model T on the mountainside and return to Fort William for the night, highlighting the challenging terrain and the limitations of early automobiles.

Footage documenting the descent, which was accomplished in a single day, was rediscovered in 2015, offering a fascinating glimpse into this historic event.

Upon his return to Fort William, a crowd gathered to witness the improbable arrival of the Model T. After making adjustments to its brakes, Alexander then drove the vehicle back to Edinburgh.

Legend suggests that this extraordinary feat was undertaken on a dare from his father, with the threat of losing his allowance as motivation!

A Lasting Legacy: Today, a statue commemorating this incredible achievement can be seen outside the Highland Cinema in Fort William, serving as a unique reminder of the pioneering spirit and the early days of motoring.

It’s a quirky and captivating piece of local history that highlights the enduring allure and challenge of Ben Nevis.

His journey began in Edinburgh, bringing him to Torlundy (the location of Highwinds) and then on to Fort William, the base for his audacious attempt on the UK’s highest peak.

The ascent up the Pony Track from Glen Nevis was a significant undertaking, taking Alexander five days to reach the summit. Each day, he would leave the Model T on the mountainside and return to Fort William for the night, highlighting the challenging terrain and the limitations of early automobiles.

Footage documenting the descent, which was accomplished in a single day, was rediscovered in 2015, offering a fascinating glimpse into this historic event.

Upon his return to Fort William, a crowd gathered to witness the improbable arrival of the Model T. After making adjustments to its brakes, Alexander then drove the vehicle back to Edinburgh.

Legend suggests that this extraordinary feat was undertaken on a dare from his father, with the threat of losing his allowance as motivation!

A Lasting Legacy: Today, a statue commemorating this incredible achievement can be seen outside the Highland Cinema in Fort William, serving as a unique reminder of the pioneering spirit and the early days of motoring.

It’s a quirky and captivating piece of local history that highlights the enduring allure and challenge of Ben Nevis.

1929

The British Aluminium Company

A significant feat of engineering in the Fort William area was the ambitious hydro-electric construction project undertaken by the British Aluminium Company, completed in 1929.

This large-scale initiative involved the creation of dams and an extensive network of underground pipework designed to harness the power of water for their aluminium smelting operations.

Millions of litres of water were ingeniously channeled from as far afield as Spey Dam, through Loch Laggan Dam and Loch Treig, before being directed through miles of tunnels excavated beneath the imposing Grey Corries, Aonach Mor, and Ben Nevis.

The scale of this project is still evident in the landscape today. Keen-eyed visitors studying local maps may notice trails marked as the “Puggy Line.”

This name refers to a narrow-gauge railway that was essential for transporting materials and personnel during the extensive tunneling work.

The legacy of this engineering endeavor continues to shape the region, as the aluminium smelting plant still operates, powered by the renewable hydro-electricity generated through this very system.

Exploring the Evidence: While the dams and tunnels themselves are largely functional infrastructure, the presence of the “Puggy Line” trails offers a tangible link to this important industrial history.

These trails often provide unique perspectives of the landscape and serve as a reminder of the immense effort involved in this early 20th-century project that harnessed the natural resources of the Highlands.

This large-scale initiative involved the creation of dams and an extensive network of underground pipework designed to harness the power of water for their aluminium smelting operations.

Millions of litres of water were ingeniously channeled from as far afield as Spey Dam, through Loch Laggan Dam and Loch Treig, before being directed through miles of tunnels excavated beneath the imposing Grey Corries, Aonach Mor, and Ben Nevis.

The scale of this project is still evident in the landscape today. Keen-eyed visitors studying local maps may notice trails marked as the “Puggy Line.”

This name refers to a narrow-gauge railway that was essential for transporting materials and personnel during the extensive tunneling work.

The legacy of this engineering endeavor continues to shape the region, as the aluminium smelting plant still operates, powered by the renewable hydro-electricity generated through this very system.

Exploring the Evidence: While the dams and tunnels themselves are largely functional infrastructure, the presence of the “Puggy Line” trails offers a tangible link to this important industrial history.

These trails often provide unique perspectives of the landscape and serve as a reminder of the immense effort involved in this early 20th-century project that harnessed the natural resources of the Highlands.

WWII

Special Forces in WWII

During the Second World War, the rugged terrain surrounding Fort William played a crucial role in the training of Allied Special Forces.

The primary training facility was located at Achnacarry Castle, a short distance away near Spean Bridge. Recruits would arrive by train at Spean Bridge before undertaking a seven-mile march to the Achnacarry estate.

At Achnacarry, these elite soldiers underwent rigorous training in survival skills, often practicing living off the land in the challenging mountainous environment. Their training also included realistic exercises with live ammunition and even simulated opposed amphibious landings on Loch Lochy, preparing them for the realities of combat.

The men who trained in this demanding environment went on to participate in some of the most daring and significant operations of the war, including the D-Day landings and the St Nazaire Raid.

The innovative training philosophies and techniques developed at Achnacarry in the Scottish Highlands continue to influence Special Forces training doctrines around the globe today.

Exploring the Legacy: While Achnacarry Castle remains a private residence, its historical significance is undeniable.

Visitors interested in this aspect of World War II history can learn more at local museums, such as the West Highland Museum in Fort William, which often features exhibits related to the Special Operations Executive (SOE) and Commando training in the area.

The landscape itself, particularly around Achnacarry and Loch Lochy, serves as a silent testament to the bravery and dedication of these wartime heroes.

The primary training facility was located at Achnacarry Castle, a short distance away near Spean Bridge. Recruits would arrive by train at Spean Bridge before undertaking a seven-mile march to the Achnacarry estate.

At Achnacarry, these elite soldiers underwent rigorous training in survival skills, often practicing living off the land in the challenging mountainous environment. Their training also included realistic exercises with live ammunition and even simulated opposed amphibious landings on Loch Lochy, preparing them for the realities of combat.

The men who trained in this demanding environment went on to participate in some of the most daring and significant operations of the war, including the D-Day landings and the St Nazaire Raid.

The innovative training philosophies and techniques developed at Achnacarry in the Scottish Highlands continue to influence Special Forces training doctrines around the globe today.

Exploring the Legacy: While Achnacarry Castle remains a private residence, its historical significance is undeniable.

Visitors interested in this aspect of World War II history can learn more at local museums, such as the West Highland Museum in Fort William, which often features exhibits related to the Special Operations Executive (SOE) and Commando training in the area.

The landscape itself, particularly around Achnacarry and Loch Lochy, serves as a silent testament to the bravery and dedication of these wartime heroes.

1989

Nevis Range

The landscape around Fort William has continued to evolve in its significance for recreation and tourism.

A key development was the opening of the Nevis Range in 1989, establishing a ski resort on the slopes of Aonach Mor.

This marked a turning point, transforming Fort William into a year-round holiday destination, attracting visitors for winter sports as well as the traditional summer activities.

Building on its mountainous terrain, the Nevis Range further diversified its offerings in 1994 with the development of dedicated mountain biking tracks.

These trails quickly gained international recognition, and the Nevis Range has since become one of the most famous mountain biking destinations globally, regularly hosting prestigious events such as the Downhill Mountain Biking World Cup.

A Modern Transformation: The story of the Nevis Range illustrates the ongoing adaptation of the Highland landscape to new forms of recreation and tourism.

From its geological origins to its role in wartime training and now as a premier outdoor adventure centre, the area around Fort William continues to hold historical significance while embracing modern activities.

A key development was the opening of the Nevis Range in 1989, establishing a ski resort on the slopes of Aonach Mor.

This marked a turning point, transforming Fort William into a year-round holiday destination, attracting visitors for winter sports as well as the traditional summer activities.

Building on its mountainous terrain, the Nevis Range further diversified its offerings in 1994 with the development of dedicated mountain biking tracks.

These trails quickly gained international recognition, and the Nevis Range has since become one of the most famous mountain biking destinations globally, regularly hosting prestigious events such as the Downhill Mountain Biking World Cup.

A Modern Transformation: The story of the Nevis Range illustrates the ongoing adaptation of the Highland landscape to new forms of recreation and tourism.

From its geological origins to its role in wartime training and now as a premier outdoor adventure centre, the area around Fort William continues to hold historical significance while embracing modern activities.